Amblyopia is poor vision in an eye that did not develop normal sight during childhood. It is sometime referred to as “lazy eye.” Usually only one eye is affected by amblyopia but, rarely, both eyes can be affected. The condition affects 2–4% of all children and is correctable if diagnosed and treated early.

Normal vision is not present at birth. As a child uses his eye, the visual system matures and normal vision develops. This maturation requires that a strong connection develop along the nerves that travel between the eye and the brain. The process of visual development continues for about the first eight to nine years of life, and it is most rapid during the first few years.

Amblyopia—poor vision in an eye—develops when the process of visual maturation is interrupted. If left untreated, the resulting poor vision is permanent. If treated before the end of visual maturation, however, the poor vision can be improved. Amblyopia is not always easy to detect without an eye examination. Frequently, children will not notice when they do not see well in one eye and parents will not see anything unusual about the eyes unless strabismus (misalignment of the eyes) is present.

Amblyopia is a lack of normal development of the neural connections in certain brain cells that are responsible for vision. While this lack of development can be permanent if left untreated, it can also be reversed if proper treatment is instituted in time.

Amblyopia may result from any of the following causes:

Poor vision in a child is not necessarily from amblyopia which specifically refers to abnormal best-corrected vision in an eye. Thus, if vision is measured to be poor in an eye because of myopia, and that eye sees 20/20 once glasses are prescribed, then amblyopia does not exist. Also, poor vision in one eye may result mainly from structural problems, e.g. a retinal detachment, and thus amblyopia may not be the primary reason for the decreased vision.

It is imperative that each child receive screening eye exams frequently throughout childhood. This is usually done by the primary care physician during the first 3–5 years and also by the schools starting in preschool. If a child is not receiving these routine checks, then he should be examined by an ophthalmologist, preferably by the age of three. If a family history of amblyopia or strabismus exists, then a child should be screened by age one to two years.

Although vision cannot be tested using an eye chart in infants and young children, an ophthalmologist can still estimate a child’s vision by examining visual behavior. Of particular importance is evaluating the visual behavior in one eye compared with the other. If amblyopia is detected, then a thorough search for a cause (see above) is undertaken with a complete, dilated eye examination.

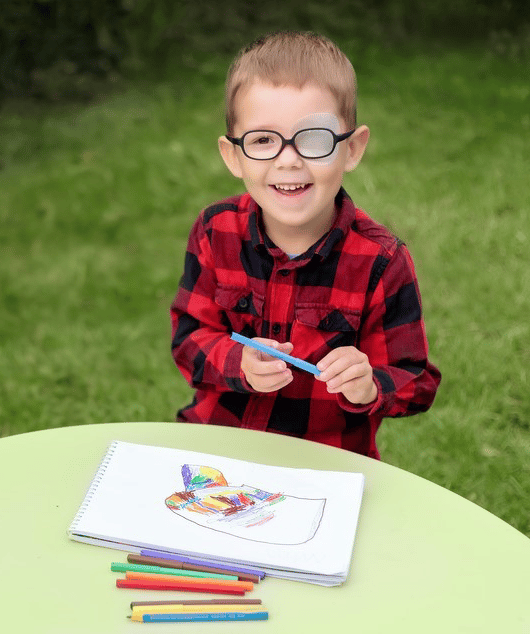

Treatment of amblyopia mainly involves forcing a child to use his “weak” eye. Often this is accomplished by patching or occluding the good eye. The amount of patching is determined by the type and severity of the amblyopia. As vision improves, the amount of patching is generally decreased. Sometimes part-time occlusion must be carried out for several years, up until the end of visual development, so that the amblyopia does not recur. If patching the eye is unsuccessful because of skin allergy to the patch or lack of compliance, than an eye drop that blurs the good eye can be used. This tends to be successful only if vision in the amblyopic eye is not severely reduced.

Glasses are sometimes needed to treat amblyopia if a significant refractive error exists. In some situations, glasses alone may correct the amblyopia, but some type of occlusion is usually needed. An occlusive foil can be placed directly on the spectacle lens of the good eye in a child who wears glasses, but parents must make certain that the child does not peek around the foil with his good eye.

If eye muscle surgery is required to correct a misalignment problem in a child with amblyopia, occlusion is usually instituted before the surgery to improve the likelihood of a good outcome. Occlusion is often still required even after surgery. Similarly, if a cataract or other structural problem with the eye is surgically corrected, occlusion and/or glasses will still usually be necessary after the surgery to treat amblyopia.

Treatment of amblyopia requires great effort on the part of both parents and child. Most children do not want to have their good eye occluded and so parents need to convince children of their need to comply with treatment. Reward systems or patching a favorite stuffed animal’s eye are just a few “tricks” that can be helpful. Learning in school may be difficult when the good eye is occluded and thus school-time patching is not common and is usually done only in cases when full-time occlusion is essential.

If amblyopia is not treated before the end of visual development, then there is very little hope of vision ever improving in the amblyopic eye. Generally speaking, the earlier in a child’s life that amblyopia is treated, the better the results. Recent studies, however, have shown that amblyopia can still be treated into teenage years in some situations.

Not only does amblyopia leave a person with reduced vision in one eye, but it also decreases depth perception. Also, if vision were ever to be lost in the good eye, then a person would be left with a lifetime of poor vision. For this reason, people with poor vision in one eye, whether it be from amblyopia or other causes, should always wear protective lenses to guard against ocular trauma and should have regular eye examinations to screen for diseases in the good eye.

Wheaton Eye Clinic’s unparalleled commitment to excellence is evident in our continued growth. Today we provide world-class medical and surgical care to patients in six suburban locations—Wheaton, Naperville, Hinsdale, Plainfield, St. Charles, and Bartlett.

(630) 668-8250 (800) 637-1054